In 2004, Dina Cappiello, a reporter for the Houston Chronicle, investigated air pollution in Manchester and other neighborhoods along the Ship Channel. The article, “In Harm’s Way,” won national accolades, including the Kevin Carmody Award for Investigative Reporting. Then newly elected Mayor Bill White took on air pollution as one of his signature efforts. Ten years later, the question is, did he succeed? Are Houstonians still in harm’s way?

The 2004 Chronicle study found levels of the carcinogens benzene and 1,3-butadiene high enough to pose a threat to public health. Consider this excerpt from the report:

At 49 of the 100 locations where the newspaper hung air monitors, attaching them to structures such as windowsills, clotheslines, swing sets and Christmas light strands, the quantities of up to five different chemicals would have exceeded levels considered safe in other states with stricter guidelines for air toxics. Unlike the more well-known air pollutants that cause asthma and respiratory effects, the compounds found at elevated levels by the Chronicle have all been linked to cancer. More specifically:

--- Levels of the human carcinogen benzene were so high in Manchester and Port Neches that one scientist said living there would be like "sitting in traffic 24-7."

--- Eighty-four readings measured by the Chronicle were high enough that they would trigger a full-scale federal investigation if these communities were hazardous waste sites.

--- Some compounds detected by the Chronicle, such as the rubber ingredient 1,3-butadiene found at four homes in the Allendale area near Manchester, if inhaled over a lifetime at the concentrations found, could increase a person's chances of contracting cancer, according to federally determined risk levels. Concentrations here were as much as 20 times higher than federal guidelines used for toxic waste dumps.

The startling numbers from the report quickly generated pressure on a mayor who had previous experience with air quality advocacy. Mayor White had served as head of the Greater Houston Partnership Clean Air Committee before his election. He spoke about clean air as good for business and would tout it as “a moral and ethical issue” during his time in office.

“Local government has traditionally played only a minor role in regulating airborne toxic pollutants; however, from 2004 to 2009, the City of Houston implemented a novel, municipality-based air toxics reduction strategy,” writes Rebecca Bruhl, Associate Director of the Environmental Health Service at the Baylor College of Medicine.

Mayor White successfully revised the joint air-program contract between Houston’s Bureau of Air Quality Control (BAQC) and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) so that the city could take action against air-pollution-law violators instead of simply citing and referring them to TCEQ. Negotiations for the contract renewal broke down when TCEQ wanted this authority back, however, and the city opted to undertake its own air-quality program in September 2005, sacrificing significant TCEQ funding. Houston first tested its new authority by bringing a civil suit against Texas Petrochemicals, the probable source of East Houston’s elevated 1,3-butadiene (a rubber ingredient) concentrations and among the only major plants located within city limits.

Texas Petrochemicals signed a voluntary agreement with TCEQ promising to cut their emissions in half in three years, but the city, dissatisfied, successfully obtained a contract that legally bound Texas Petrochemicals to cut emissions. Mayor White’s administration identified essential flaws in the state regulatory system, specifically that obtaining permits did not require ongoing monitoring of a facility’s emissions. The city acquired grants for a mobile air-monitoring laboratory and infrared cameras that detect leaks visually. As one BAQC manager summarized the new strategy, “with increased monitoring capacity, we were able to build an inventory to figure out where to go and who is responsible for what.” The city did not file any more suits during Mayor White’s term; however, when White sought City Council approval to sue other companies, they quickly complied with the city’s requests.

Realizing that most of the problematic benzene sources were not within city limits, Mayor White sought regional cooperation for his Voluntary Benzene Reduction Plan, but no plants agreed to adopt it. White then attempted to revise a nuisance ordinance to allow the city to sue bordering municipalities that were emitting hazardous pollutants in violation of EPA’s standard, and to render certain violations of state law enforceable under the municipal code, but the Business Coalition for Clean Air (BCCA) Appeal Group challenged this move in court and won.

Mayor White then took his fight to senior Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) leadership in Washington. EPA officials agreed to join BAQC in monitoring the city’s emissions. In what was potentially the city’s most significant victory since the Texas Petrochemicals suit, in April 2009 EPA announced they were revising their protocol.

So did Mayor White’s leadership bring about a reduction in the levels of air toxics?

“Overall the trend has been good with a significant decrease from 2004 to 2011,” says Don Richner, an air quality expert at the city’s Department of Health and Human Services. He adds, “We are not sure what the future holds with the expansion of the port.”

Larry Soward, a former Commissioner at the TCEQ, concurs. “I think Mayor White’s aggressive approach counts for some of those significant reductions,” he says, though adding that “the people in Manchester still need to worry.”

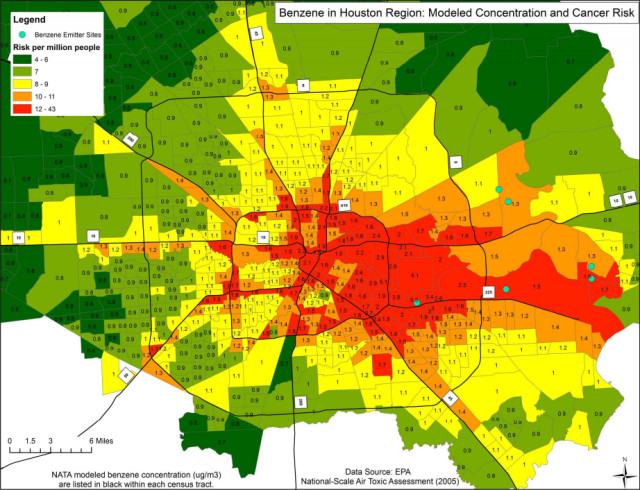

Graphs from industry-funded Houston Regional Monitoring show a dramatic reduction in benzene since 1988. Dr. Bruhl, however, notes that the graphs “show trends in ambient concentrations at their monitors, but these clearly don’t tell the whole story. Annual averages mask spatial and temporal variation.”

Better understanding of air toxics is not likely to come about without a constant, high level of public awareness and scrutiny of TCEQ.

Adrian Shelley, Executive Director of Air Alliance Houston, writes, “If you've ever wanted to tell the TCEQ what you think about air monitoring in Texas, now is your chance. Did a monitor near you move? Are more monitors needed in your community? Are you concerned about the air quality in your neighborhood? Tell the TCEQ by submitting comments on the 2014 Annual Network Monitoring Plan now through next Thursday, June 19. Submit comments by email to: monops@tceq.texas.gov. Or by mail to: Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, P.O. Box 13087, Attention: Stephanie Ma, MC-165, Austin, Texas 78711-3087.”

More >>>

"What's your cancer risk in Houston? (Bigger than in Dallas)" by Raj Mankad, OffCite, February 24, 2014; "Growing Risks: Balancing Houston's Prosperity and Air Quality, Part 1" by Larry Soward, OffCite, February 26, 2014; "Growing Risks: Balancing Houston’s Prosperity and Air Quality, Part 2" by Larry Soward, OffCite, March 4, 2014